Last week, we discussed an array of possible factors that could contribute to a rise in inflation. These include:

- In an effort to spur the economy, policy makers have embarked on an unprecedented campaign of quantitative easing, a tool which is inflationary in nature.

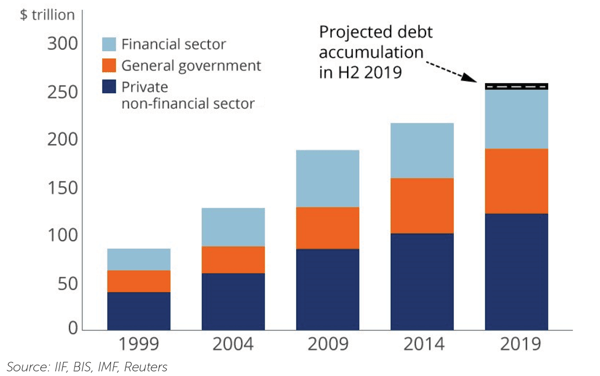

- Stimulative economic policy has pushed global debt to $255 trillion, which has roughly doubled since 2004, as evidenced by the graph below. All else equal, high debt levels lead to high inflation.

Global debt by year:

- Governments will accelerate inflation to lower the present value of debt to facilitate de-leveraging.

- Continued progress in trade negotiations, full employment, and a rebound in global growth may accelerate the pace of inflation.

While these arguments are rational, the reality of today’s low inflation environment is perplexing. So, is Buffett’s prediction for “an onslaught” of inflation invalid given the passage of time? Have astute policy makers undertaken a massive campaign of unconventional monetary policy with no consequences?

We doubt it.

The transition to an inflationary environment may require an exogenous shock. The shock could come from a recession, credit crunch, escalation of the trade war, political change viewed as negative for the economy, conflict, black swan events, etc. In our view, one or more of these scenarios has a modest chance of occurring in the coming years given where we are in the economic cycle and the political climate.

For example, if a recession occurs, we’d expect debt levels to meaningfully increase as automatic stabilizers such as lower tax rates, unemployment insurance, and higher use of government assistance programs such as Medicaid take hold. Fiscal spending would be used to stimulate the economy which would push debt even higher. Central banks will use what little “ammunition” is left, and governments may attempt to devalue their currency in order to spur growth.

In the end, economies (perhaps our own) may be left with higher debt levels, weaker currencies, and the exhaustion of policy options. A potential result is eroding faith in the fiscal / monetary situation. Individuals might then assign a discount to our currency (i.e. require more dollars per transaction), which would be inflationary in nature. Additionally, the real cost of capital could then increase.

Assuming the inflationary pressure isn’t extreme (e.g. what the United States experienced in the 1970’s), we believe this scenario may be positive for the global economy despite the short-term pain of an exogenous event such as recession. Over the long run, the present value of debt should decline meaningfully and policy makers would gain valuable “ammunition” by hiking rates and shrinking their balance sheets to curtail inflation. This should give individuals greater faith in the underlying fiscal / monetary position – thereby improving the economic outlook and the movement of inflation to a lower and healthier level. The labor force might also benefit in the long term as businesses substitute higher cost capital for labor which will drive wage growth.

We hope the unwinding of the global debt burden and central bank balance sheets will be manageable. That said, there are bound to be casualties from such a shift. Investors heavily weighted in cash and fixed rate assets will suffer in an inflationary environment. Additionally, there will be a large swath of companies whose fundamentals and share prices would deteriorate under this environment. We will elaborate on which types of companies could stand to benefit from a return of inflation in a future blog – be sure to subscribe below.

Interested in reading last week's blog? Click here: The Potential for a Return of Inflation, Part 1

If you would like to be notified when we release new blogs, please let us know!

Just complete the form on this page and we will deliver our insights to your inbox once per week.